Hurtling Through a Beethoven Hurricane

Year 2, Week 7, in one pianists' journey to perform the 32 piano sonatas of Beethoven.

It was a white-knuckle drive across the Confederation Bridge to our home in Prince Edward Island. I’ve never driven it when it was so windy. Its eight-mile span is supposed to be driveable in ten minutes, but with the “Wind Warning” status, the speed limit was reduced to 60 kph, and we endured over fifteen minutes of me holding fast to the wheel and audibly praying, while my daughter muttered over and over to herself, “It’s going to be okay”.

Long ago I learned that in times of highly spiked performance anxiety, such as, say, playing the finale of the Rachmaninoff Concerto No. 3 in live performance, it’s helpful to remember to mentally come up for air and look around at the big picture. I remember such an instant when I was twenty, playing it for the first time for a packed audience. In that moment I had the cheeky thought, “I’m the only one here who can do this”. The hubris of youth!

This at the outset of a life journey of learning absolutely the hard way, with many hard falls, that performing is service, not an ego trip.

These days, when I take a glance around while performing, it is to wonder at the grandeur of life around me, in which I have happened to become a swirling speck onstage. Others have designed and carefully built this hall to hold this music. They have revered this music as much as I do. Others made this piano, came to this concert, organized this staff, recorded this livestream, donated to this cause. Still others are choosing the front row and whooping spontaneously after the ride over rapids that is Beethoven’s “Moonlight” sonata finale.

On the Confederation Bridge, going home from my Halifax concert, 60 metres above sea level in a windstorm, I remembered to glance around a couple of times. Monstrous whitecaps raced in all directions to the horizon over a green ocean. Clouds from black to gray to white filled the sky, rainbows materializing and dematerializing between them. Sometimes a white haze blew horizontally across us; other times we saw tall white shafts processing offside. Eventually the distant cliffs of our island appeared, shining yellow in places, shadowed in others, with patches of bright orange.

We were on our only fixed link to the democracy of Canada.

Now, they say, we Earthlings are all living in a Trumpian Era. Or is it a Climate Change Era? Which has greater portent, the revolutionary populist turning tyrant, or the natural world storming us?

I’m thinking about storms because my next all-Beethoven concert is the one I’ve named “TEMPEST”. It was the first all-Beethoven program I ever played, in the fall of 2023, and it’s the one that convinced me to go ahead and learn all the other sonatas.

I designed “TEMPEST” to be a tribute for a group of friends who I wanted to thank. These friends – Dianne, Jeff, Nathan, Linda, Alison, Greg, and Cathleen – had helped my daughter and me during the 15 days we went without power or water after hurricane Fiona. I wanted to invite them all to a house concert and party on the one-year anniversary of the day Fiona hit our island on September 24, 2022.

Fiona is on record as the costliest and most intense hurricane ever to hit Canada.

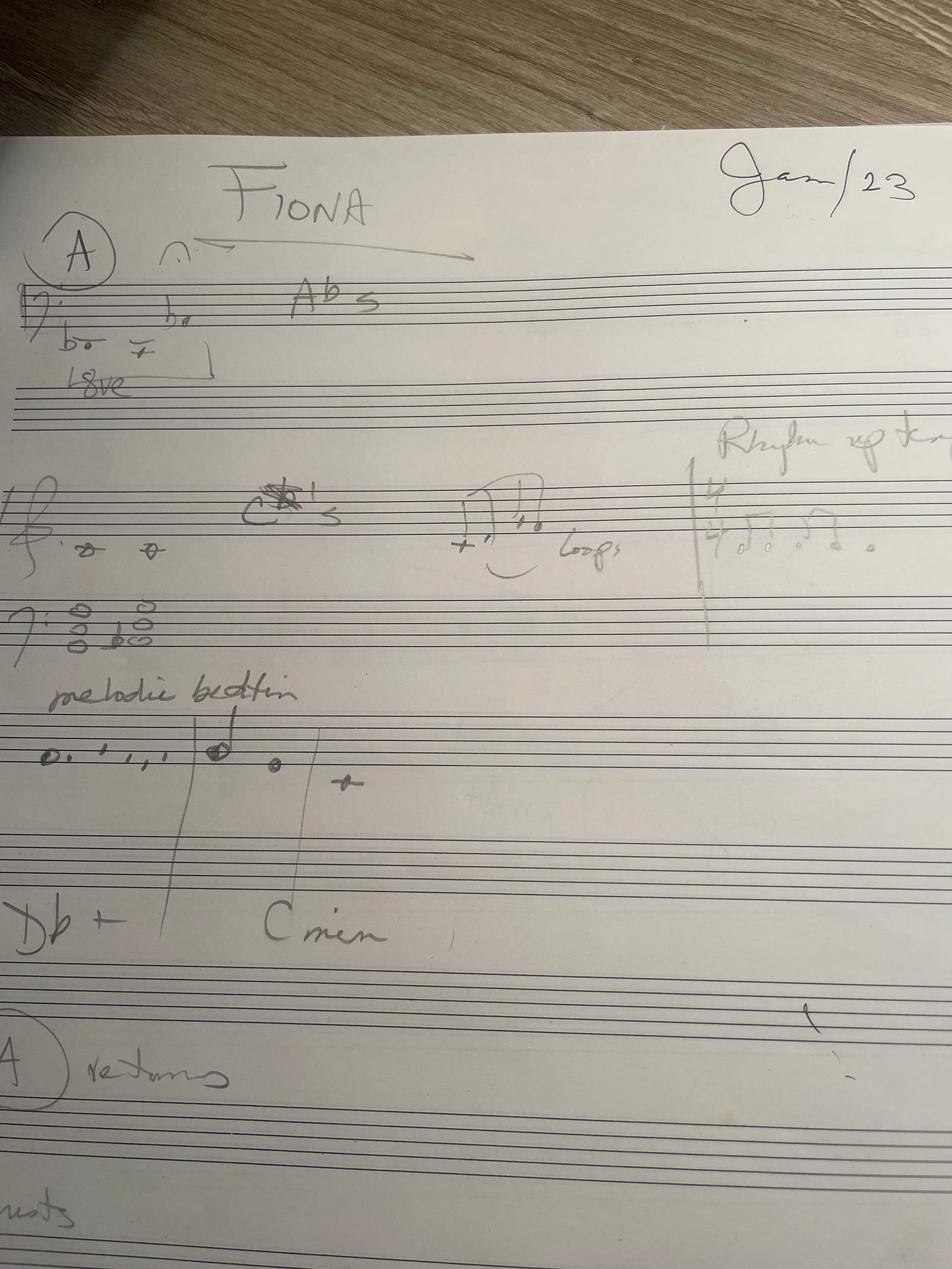

My initial thought for this concert was to compose my own piano piece called “Fiona”, and play it together with other “stormy” pieces.

I began to try to compose “Fiona” by reviewing our pics of its aftermath. We don’t have video footage because it hit during the night. I do have one short clip, just blackness. What you can hear of Fiona via the iPhone mic is on two levels: a great hiss of leaves and branches blowing at us, and beyond that, a deep freight train roar. The hiss brought back fear. The roar, terror. The clip was taken before the roar fully reached us, ripping out over 70 trees all around our house.

I tried improvising “Fiona” at the piano, and jotted down some sketches, but re-experiencing the sounds and fury of that night was simply too paralysing. I am not an experienced composer, and my still-fresh reactions to the storm were too overpowering for me to transmute into a score. I didn’t get much.

I did, however, glean something of what such a storm ought to sound like in music. Asking myself what music had such sounds, my answer was Beethoven’s “Appassionata” Sonata, Opus 57 in F minor.

What I wanted to get at was the inconsistent nature of terror: the distant rumble, the anticipatory silences, the sudden blows and thuds, and then, swooping onto centre stage, the devastating power of swirling circular movement, toppling everything in sight. What I just described there is how a hurricane reaches one, but it’s also an entirely apt description of the first page of the “Appassionata” sonata.

Beethoven has two other particularly tempestuous sonatas. There’s the so-called “Tempest” sonata Opus 31 No. 2 in D minor, and the “Pathétique” Sonata Opus 13 in C minor. Both of them were written a few years before the “Appassionata”.

All three stormy sonatas share a structure that is unique to them among Beethoven’s other sonatas. They all have a first movement, in a minor key, that begins with a halting, slow opening before exploding into a storm. After this first movement, all three go to a slow movement that, in geek language, is based on the minor submediant above the original tonic. Or in plain speech: if you sing “do-re-mi-fa-sol-la”, the second movement is based on the “la”. Notice how the “la” feels hovering, unstable, hopeful, but unfinished? That’s Beethoven’s “affect”, or chosen mood, for the slow movement. Now, for the third and final movement, try this: instead of continuing to sing upwards from “la” to “ti-do”, sing from “la” back down to “sol” and then immediately slide right down to “do”. That is how Beethoven treats the ends of these slow movements – he uses “la-sol-do” to catapult us back down into the storm for a third movement tragic finale.

Enthralled by the way Beethoven captured my personal hurricane trauma in the “Appassionata”, I ended up shelving my own “Fiona” composition and building an all-Beethoven program that would culminate in the “Appassionata”.

I started with the earlier stormy sonata, the “Tempest”. This sonata, as compared to the “Appassionata”, is more like a typical fall storm that you might walk through while it resonates with your inner tempests. Beethoven wrote it around the time he first came to grips with the fact he was losing his hearing, which meant he would have to switch from being best known as a performer-improvisor to being mainly a composer. He wrote that he was looking for a “new way” to compose. The “Tempest” is indeed tempestuous and innovative, but also a reflective, existential work.

To follow the “Tempest” sonata, rather than playing Beethoven’s third stormy sonata, the Pathétique, I programmed a respite: the so-called “Pastoral” sonata Opus 28 in D major. Its lilting themes, humour, and peasant dance rhythms are mostly comforting, if somewhat wistful. This four-movement work is more traditional in form, as though to emphasize that “life goes on” even in time of personal tragedy. But he does switch from the loveliness of D major to the “Tempest” sonata’s key of D minor for the slow movement, bringing out the undertone of existential tragedy underlying this period of his life.

After an intermission, my “TEMPEST” program ends with the “Appassionata”.

A year later, now that I’ve played all 32 sonatas, I can say that there is no other sonata in which Beethoven so completely allows himself to fly into the vortex of a raging cyclone as he does in the “Appassionata”.

Is this rage his expression of Nature, or of the disruptive geopolitics of his time, or his own fate?

In 1804, when he composed “Appassionata” the thirty-four-year-old Beethoven was making a fair copy of his new orchestra work, the “Eroica” Symphony No. 3. “Eroica” means “Heroic”. It’s difficult today to understand just how ground-breaking that symphony was: what a stick in the eye of culture. It helped me to watch the terrific 2003 BBC feature film Eroica.

Beethoven had admired Napoleon as a populist, revolutionary leader who would upend the “deep state” with its entrenched elites. You have only to walk around the historical palaces of Vienna today to see how entrenched they were. Beethoven wrote his new symphony, initially titled “Buonaparte”, as a way of doing to music what Napoleon was doing to the world order.

However, he did so in trust that innovative, democracy-minded patrons and critics would listen to it, debate it, and place it within the development of a high musical culture with its roots based in history. Plato’s Republic was one of Beethoven’s favourite books.

He trusted that Napoleon was up to something similar.

But then Napoleon, having achieved leadership and the rank of First Consul, went further. He proclaimed himself Emperor and bestowed a crown on himself. He did so by manipulation of the legal system through acts of the French Tribunate and Senate dated May 3, 4, and 17, 1804.

In that moment, Beethoven had just completed his manuscript of the symphony with its dedication to Buonaparte on the title page. Beethoven’s student Ferdinand Ries writes of going over to Beethoven’s place to give him the news:

“I was the first to bring him the intelligence that Buonaparte had proclaimed himself emperor, whereupon he flew into a rage and cried out: ‘Is he then, too, nothing more than an ordinary human being? Now he, too, will trample on all the rights of man and indulge only his ambition. He will exalt himself above all others, become a tyrant!’ Beethoven went to the table, took hold of the title page by the top, tore it in two and threw it on the floor. The first page was rewritten and only then did the symphony receive the title: ‘Sinfonia eroica’.”

A few months later, Ries continues, he took a long walk with Beethoven:

“He had been all the time humming and sometimes howling, always up and down, without singing any definite notes…when we entered the room he ran to the pianoforte without taking off his hat. I took a seat in the corner and he soon forgot all about me. Now he stormed for at least an hour with the beautiful finale of the sonata.”

This was the “Appassionata” sonata. A fixed link from history, created by Beethoven for us to navigate.

Great interpretation for whatever storms we weather. -)